Being Looked At, Being Talked About

from Essays

Remarks to incoming U.S. Fulbright Scholars to Australia

Thursday, August 23, 2012

National Portrait Gallery

Canberra, Australia

At a meeting of the college faculty an angel suddenly appears and tells the head of the philosophy department, “I will grant you whichever of three blessings you choose: Wisdom, Beauty or ten million dollars.”

The professor doesn’t hesitate for a second and chooses Wisdom.

There is a flash of lightning, and the professor appears transformed. But she just sits there, sadly staring down at the table.

One of her colleagues finally whispers to her, “Say something.”

The professor whispers back, “I should have taken the money.”

I’m happy to say to the new Fulbright scholars gathered here tonight that we’re so glad you have chosen the fellowship money, however modest it is in comparison with your talents and intellectual ambitions.

As for the wisdom, we’re hoping that you’ll offer that to us. It’s certainly been the greatest pleasure, as chairman of the Fulbright board, to be literally startled into questions, fascinating ideas and extraordinary stories through my meetings with thousands of Fulbright students, scholars and alumni around the world.

So I congratulate you on behalf of the entire Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board. And I bring greetings from President Obama and Secretary of State Clinton, who both believe so passionately in the power of Fulbright.

And let me thank the many partners in this great program, at all levels of the Australian government, within the world-class Australian university system and under the leadership of the Australian-American Fulbright Commission, chaired by Vice-Chancellor Stephen Schwartz and led by the tireless and wonderful Dr. Tangerine Holt. And thank you to my hosts and friends from the American embassy and consulates who have taken care of me all across Australia from Perth to Sydney, Ambassador Jeffrey Bleich, Deputy Chief of Mission Jason Hyland and their wonderful diplomatic team.

So here we are in the National Portrait Gallery. I love portrait galleries. They offer clues into how a country sees itself. Or how a certain official part of a country sees itself at a certain time and place. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if some government somewhere irreverently carved a slightly different name in the granite and called it the National Rogue’s Gallery? Or at least rogues and saints?

Australians from every corner are represented in this building: Officials in wigs (and I don’t just mean Dame Edna), workers in coveralls, scientists, socialites, business leaders and artists: the great, the good, the bad, the beautiful and the … not so much. The portraits here tell the stories of Australians by Australians, whether it’s a calm, elegant painting of the prime minister or the big, amorphous, blob-like sculpture you passed on your way in, which might also be a portrait of a prime minister, perhaps just after Question Time. The artist of the blob, James Angus, is, of course, a Fulbright scholar. And, come to think of it, you’d really have to call the color of it “Tangerine,” though our brilliant Commission director could never be portrayed without heat and motion.

A portrait is many things—a representation, a statement, an idealization, even an evasion, always an outright fabrication—but most of all it is a gesture, an incomplete effort toward an understanding of ourselves, where we’ve been and where we’re going. And as the great portraits here (and not here) remind us, a portrait gestures both toward the well-remembered and toward the forgotten.

And for that reason, portraits are always imbued with at least a bit of controversy. Nothing is fixed or final about them. None of them is the last word. I certainly hope that about portraits taken of me.

Some of the Americans in the room will remember, only two years ago the curators at our own National Gallery in Washington bowed to pressure and removed David Wojnarowicz’s Fire in My Belly, which was his video portrait of his religious upbringing. It was removed from exhibition because some people didn’t like what Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS, had to say, they didn’t like the kind of angry story his self-portrait told.

Or, down the street here in Canberra at the National Gallery of Australia, you can see Tony Albert’s powerful work about how people are portrayed by others – with the stereotypes, fantasies, misunderstandings and even malevolence that can happen when people want to take our pictures.

In his work, Albert collected a large series of kitsch souvenir ashtrays from all over Australia, metal, ceramic, plastic, all shapes and sizes. But when you look at them closely, you realize the images aren’t tourist maps or slogans or typical images of iconic destinations. The ashtrays are all stamped with portraits of indigenous peoples – and you suddenly get a chill realizing these ashtrays were deliberately made for cigarette butts to be stubbed out on the faces of the Aboriginal men, women and children. These were common, everyday ashtrays that many people had.

A portrait is always something of a controversy because it risks, but never fully offers, the truth. Whether idealized or actual, whether admiring or hostile, it is frozen and distilled, trying to capture what is never fully knowable. Who is that person? Who wants to know? And why?

We all know, usually much less drastically, but still urgently to ourselves, what it feels like to lose control over our image-making. A portrait is always something of a controversy because it risks, but never fully offers, the truth. A portrait risks the truth because people are always different from who we think they are or who they think they are.

But the alternative to the gestures of portraiture, to the attempts at bearing witness and telling stories about people, is silence, anonymity, disappearance.

That is the urgent meaning Oscar Wilde also intended when he wrote the now-cliched, emotional truth, “The only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about.”

But in our age of indescribable narcissism – reality TV shows and the endless assault of people’s personal broadcasts through Twitter and Facebook and Flickr and YouTube – perhaps we’re at no risk of people not being talked about – or at least not talking about themselves.

All is bared. All is out there. TMI. Too much information. (I have a running joke with people in government about how often they use acronyms. But a consular officer told me that if TMI were a government acronym it would mean “Totally my idea.”) In any case, showing us supposedly everything 24/7 isn’t the same as telling the truth or even telling us a good and necessary story. The truth is hard to find.

And so, many stories are not told. Billions of people, critical ideas, endless discoveries and rediscoveries are waiting out there – as are endlessly subtle, brave, elegant and accurate ways of telling them, ways that just might not fit into 140 characters typed with your thumbs.

So, Fulbright scholars, we are actually very eager for you to talk about yourselves, to talk about others, when what you’re trying to share is something different, something urgent, something that will do good, even if it is just to wake us up from some complacency.

Taking new portraits of people and ideas and the world means taking the risk of disagreement, of debate, of difference.

As Senator Fulbright, the founder of this program, once said, “In democracy, dissent is an act of faith.” And here you are down under, in Oz, where, as that great Australian Clive James once bragged, “Democracy works better … than almost anywhere.” A good democracy is a great place for stories, for inner worlds and out, for seeing yourself in everyone else, for reverie.

The demoi of ancient Greece were bound into a single state not only by a legal system, but by a national literature of storytelling, of portraiture: Herodotus, Sophocles, Homer. The first image of the Iliad is a portrait of a man.

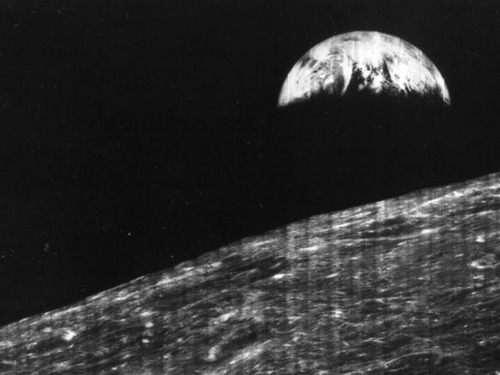

And, of course, portraits aren’t limited to the arts. Portraits are written, sung, and painted by science. Think of the archeological restoration efforts of our first images of ourselves in the caves of Lascaux or the new photograph from Mars last week shot by Curiosity – a portrait of the horizon, above which hover three tiny white lights: Earth, Venus and Jupiter—a reminder that, in the words of astrophysicist Neil Degrasse-Tyson, we’re only “a speck on a speck on a speck.”

Seeing pictures of ourselves can be humbling.

But science paints some essential portraits of us: from Darwin’s theory of evolution to that first famous photograph of the earth looking back from the moon, taken forty-six years ago today.

Like that amazing bite out of the globe hovering so fragilely in the black void over the curve of the moon, every portrait is a map, tracking a borderless place of undiscovered depths, uncharted areas of experience and understanding that will never be fully knowable. We will never exhaust the stories that need to be told, the experiences we need to document.

As Fulbrighters, you will have the obligation and the thrilling privilege to make unique portraits, stories, and maps of your journey—as did the over 300,000 Fulbrighters before you. And it very much matters that these are your journeys, your investigations, your stories. It is only the entire array, the interconnection of all your stories, that offers the rest of us some glimpse of accuracy.

Think of aboriginal Dreamtime, which the many tribes here still tell of in the “Dreamlines,” those songs that record the travel of the legendary gods across Australia as they sang out, in the words of the great traveler writer Bruce Chatwin, “the name of everything that crossed their path—birds, animals, plants, rocks, waterholes—and so singing the world into existence.”

A portrait can be a reverie.

As Chatwin wrote in The Songlines, one of the many, many great books about this country that have nourished me over the years, “Each totemic ancestor, while traveling through the country, was thought to have scattered a trail of words and musical notes along the lines of his footprints,” which not only mapped Australia, but wrote it into existence in the songs of those living there. “In theory,” he concludes, “the whole of Australia could be read as a musical score.”

I like the way a Warakurna indigenous artist put the same idea: “All the stories got into our minds and eyes.” Stories get inside us.

Let the stories of Australia get inside you, notice how these stories change you. Then you change them, make them personal and release them again. Or, as the much-mourned Ray Bradbury, that great, generous, novelist with an uncanny ability to see into our future, frequently said, “Pay it forward.”

Just keep in mind that we are only a speck on a speck on a speck. And, although all of our talents are limited, we learn far more than we teach. As another Fulbrighter, Rachel Smith, told me a few months ago, “Fulbright is not about changing the world. It is about sharing the world.” And, of course, where did she have her Fulbright? Right here in Canberra at ANU.

Portraits? Stories? Maps? Science? Music? Australia? Fulbright?

I’ve meant to thread together some themes of how we are connected, how great our responsibilities are to connect to others, to share with one another, in our complicated, troubled, but hopeful world.

So I leave you with what I hope will be a lifelong task: Make portraits and maps of the ways you experience this country, understand its songs, tell your stories and listen for stories you will find here.

Then bring all of it back with you. You didn’t get $10 million dollars, but we did choose you to go find wisdom. We will be eagerly waiting to learn what you’ll bring back home, your portraits, your self-portraits, and you.