Seeing Fire in the Clouds

from Essays

Essay on the winner of the 2013 TED Wish Prize

TED/The Huffington Post

Long Beach, California

February 27, 2013

Last night, as I listened to famed educator Dr. Sugata Mitra speak at the TED Conference, I thought about the impossible. Mitra had just won TED’s 2013 Wish Prize: $1million to do something powerful, dramatic, profound to make the world a bit better and to inspire broad, grassroots participation across the globe.

Dr. Mitra was talking about children. He was describing some experiments he’s done that led him to develop SOLE—self-organizing learning environments. The idea came out of Mitra’s thinking about a critical paradox in education: how difficult it is to find good teachers where they are needed most, in low-income and rural areas where people are too poor and the neighborhoods too dangerous, too out of the way to attract the necessary educators. It’s not only difficult, it’s often impossible.

He is fond of quoting the science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke: “If children have interest, then education happens.” There’s no fiction in that. Just truth and common sense—that Dr. Mitra has backed with serious science and research. But how do you get kids interested if there are no teachers for them?

That got me thinking about something else Arthur Clarke said that I love to quote: “The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.” And that’s what Mitra believes we must do to to make the radical changes necessary for education in this new century: we must venture into the impossible. That’s what Mitra’s experiments did, and out of the impossible, he came back with the incredible: an approach to education in which children learn to teach themselves, in small groups, everything from English to brain science. A little speculation, a little science fiction, a lot of dedication—and suddenly we go from paradox to the possible.

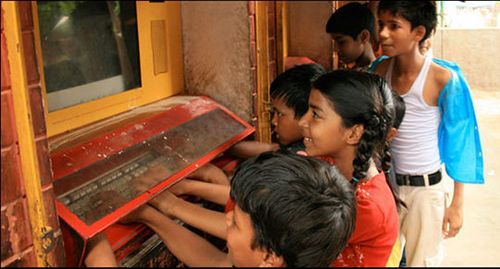

In a world of cynicism and defeat about education, with reduced budgets and restricted approaches to learning, where innovation is too often kept at arm’s length by lotteries and districting, Dr. Mirta’s SOLE idea emerged out of his famous hole-in-the wall experiments. It is an innovation that emerged out of Mirta’s almost child-like playfulness and quiet observation, a radical openness to just watching poor kids and listening to them to see what they did on their own with computers—but without assumptions, without vested interests, without teachers.

Some of our most interesting accomplishments today meet, like Dr. Mirta’s learning environments, at the intersection of technology and education: the MOOCs of Harvard and Penn, where 30,000 students, including a U.S. Senator, are studying modern poetry with professor Al Filreis; MIT, Harvard, and Berkeley’s collaborate, web-based learning initiative, EdX, is another. These online strategies are new, but have already accomplished much. However, with Dr. Mitra’s approach, we can finally begin to see a web-based learning system for children that is limited only by our questions and curiosity. The more children ask, the more they seek to learn, the more what Mirta calls a virtual “school in the clouds” can grow.

For all the newness of this approach, what interests me most is the history of Dr. Mirta’s experiments and the debt they owe to the thinking of one of the 19th century’s greatest educators: Maria Montessori.

While studying in Rome, Montessori isolated at a young age the biggest problem in education: the lack of focus on the student. As she said later, “No social problem is as universal as the oppression of the child.” Montessori also said, “Our care of the child should be governed, not by the desire to make him learn things, but by the endeavor always to keep burning within him that light which is called intelligence.” More than one-hundred years later, there are strong echoes of Montessori in the passionate and provocative philosophy Dr. Mitra espoused in his TED wish: that education should be less about teachers teaching and more about children learning—by teaching themselves and one another.

Mitra developed his philosophy by watching children in slums who had no teachers and still showed remarkable abilities to learn. He discovered what children already know: there are virtues in some cruel necessities. Children can teach themselves if we let them.

It’s a philosophy that’s actually being put in practice all over the United States and the world. In the U.S., educators like Geoffrey Canada in Harlem have renewed the 19th century’s spirit of innovative, self-directed education, creating classrooms that draw their energy on the freeflow of community, rather than the intense, rote question-and-answer classroom.

As Marie Montessori said more than a hundred years ago, education must be about keeping the flame of curiosity burning. It’s a powerful metaphor. And, in fact, we heard it at another TED Talk yesterday when Stuart Firestein quoted the poet W.B. Yeats: “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.” If that seems eloquent but too intangible when the issues of education policy and cost seem so complex and daunting, I think it’s worth thinking about in the simple terms of that old proverb about how it is better to light one candle than to curse the darkness.

TED’s million-dollar prize will certainly light quite a few candles. But for each of us, it really only needs to be one candle at a time—one child at a time, whose curiosity we’ll take responsibility for nurturing. Forget all the testing and policy-making and top-down education factory building. Just one child, one flame. From each of us. And suddenly the sky will brighten, Mitra’s school in the cloud will billow with illumination. And the impossible might just become possible. We certainly need it to be.